Don’t take tunneling for granite: Building Metro under Georgetown

Georgetown from the Key Bridge by Jeff Vincent licensed under Creative Commons.

This was the second in a two-part series. Read part one.

This summer, the Washington region will consider multiple alternatives for future Metro services in the downtown core. Four of the six alternatives involve building a new Metro line from Rosslyn to Georgetown, Mount Vernon Square, Union Station, and beyond.

This new line is essential, but it will face multiple challenges stemming from the rocks and sediments it will have to be built through. Whichever build alternatives you happen to favor, we should address these challenges proactively. Incorporating future-proofing elements into the design of the core segment will unlock the greatest benefit this project can provide.

Looking underground to understand Metro’s expansion proposals

In response to the first installment in this series, I received some thoughtful questions from readers by email, asking for more details. Why do the building foundations around Rosslyn block a connecting wye track from Courthouse to Arlington Cemetery? Why was the Blue-Yellow loop shelved? What other alternatives has WMATA considered?

The best answers are found in WMATA’s own documentation, especially public meeting presentations from the Connect Greater Washington and Regional Transit System Plan studies in years past, and the preliminary phase of the current Blue-Orange-Silver (BOS) study. These offer some specific details, but they won’t (for example) tell you which building at which address in Arlington has a deep enough foundation to block a hypothetical tunnel diverging from the Orange Line east of Court House.

Part of the problem, I think, is that it’s difficult to visualize what occupies the 3D space below ground, because we can’t see it. It’s one thing to be told that some large structure is buried over yonder; it’s another thing to picture that structure in your mind’s eye, with a good sense of where it begins and ends. It’s a skill geologists learn, but urban planners and policy makers don’t necessarily encounter. As an illustration, I’d like to take a deep dive (both literal and figurative) into the subsurface around the core segment shared by all four BOS build alternatives, and discuss how the geology of the Washington region might affect the construction of this new line.

The geotechnical challenge, part one: Digging through solid granite

The BOS core segment will face all the same engineering challenges of any subway tunnel: utility relocation, street closures, maintaining adjacent building foundations, etc. But it also faces a challenge that the other segments of the proposed build alternatives likely would not: the material it will need to dig through.

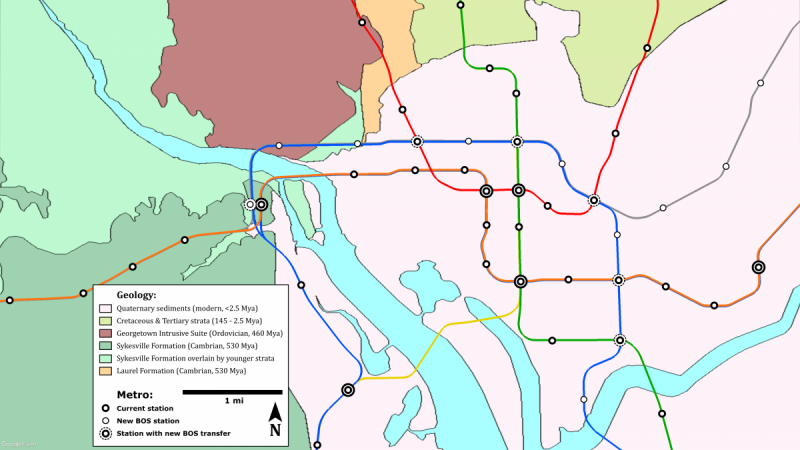

Simplified geologic map of downtown DC, overlain with existing Metro lines and the approximate alignments of two proposed BOS alternatives. Geologic units based on (https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_277.htm).

For most of the alignment, geology presents no major obstacle. The portion east of 26th St NW would be dug through Quaternary sediments. These consist of gravel, sand, silt, and clay deposited in stream channels and shallow coastline in the last two million years or so as sea levels rose and fell during repeated climactic warm periods and Ice Ages. Sediment is an easy material to construct subway tunnels in: excavators and tunnel shields are built to chew through it, and the main technical challenges involve utility relocations and adjacent building foundations.

The most challenging section would be from Rosslyn to West End. Here, both the tunnels and the Georgetown station box would need to be dug through a unit of hard igneous rocks called the Georgetown Intrusive Suite. Formed during the assembly of the supercontinent Pangaea 460 million years ago, this massive formation was emplaced as the underside of one continental block melted into viscous, silica-rich magma, that then bubbled up through the overlying rock strata, cooling and solidifying as it went.

The result is essentially a colossal pillar of solid granite (technically tonalite, for any fellow geoscientists reading this), running from the Potomac all the way north through the District and Maryland into southern Pennsylvania. Granite is among the hardest rocks to dig through, often requiring underground blasting, a time-consuming, expensive, and potentially hazardous process.

The geotechnical challenge, part two: Digging really deep vs. a new bridge crossing

Worse, the proximity of the future Georgetown station to the Potomac River will pose challenges beyond the Georgetown Intrusive Suite, particularly at Rosslyn. The new Rosslyn station itself would be dug into the Sykesville Formation, sedimentary rocks that formed around half a billion years ago during the early Paleozoic.

Though hardened and metamorphosed by tremendous pressure from overlying material, the Sykesville Formation should not be too challenging to dig a station box or tunnels into with the aid of specialized equipment. However, the Rosslyn II station and its approach tunnels will need to be dug around those of the current Rosslyn I station, crossing either above or below the existing tunnels. Rosslyn I sits 117 feet below ground level, so that its northern approach tracks can descend even further to pass 97 feet beneath the river bottom.

The deeper Rosslyn II is built to pass beneath the existing tracks, the more rock must be excavated on both sides of the river, and the greater the challenge of excavating it. The Silver Line Express alternative would be the worst affected, since its new express tunnels will require the greatest amount of digging. But in any deep alternative, the Georgetown station would likely need to be at least 100 feet below ground level, with both the station itself and its attendant elevator, escalator, mezzanine, and ventilation shafts all needing to be blasted out from within the Georgetown Intrusive Suite.

On the other hand, building Rosslyn II shallower than Rosslyn I could also impose challenges. The new line would likely need to surface and cross over the Potomac on a bridge before entering another tunnel on the north side of the river. While a bridge crossing would enable the Georgetown station to be built as close to ground level as possible and thus minimize excavation in such hard granitic rock, it would likely require the Park Service to approve a new crossing over the GW Parkway and the C&O Canal.

A near-surface Rosslyn II could also run into similar problems with building foundations that nixed the Rosslyn Wye. Finally, while near-surface construction could use inexpensive cut-and-cover excavation, it also has greater potential to disrupt the activity of the surrounding neighborhoods.

Readers who’ve studied (or remember) Metro’s construction history may hear echoes of the Red Line. The western branch of the Red Line also had to dig through the Georgetown Intrusive Suite, from just north of Dupont Circle where it dives under Rock Creek, all the way to Tenleytown. This section of the Red Line took over a decade to complete, while the rest of the system expanded rapidly in all directions, and only north of Tenleytown did the pace of Red Line construction accelerate.

Moreover, this segment had to be built incredibly deep, because the Park Service vetoed a proposed lower deck for Metro on the Connecticut Ave bridge. And if you’ve ever lamented the water damage at Van Ness or Cleveland Park, the Georgetown Intrusive Suite earns your additional ire: it’s just porous enough to let a tiny amount of water seep through, and the hardness of the rock combined with the stations’ depth prevent retrofitting to add waterproofing structures that line station vaults elsewhere.

It is likely that this short section from Rosslyn II through Georgetown to West End will encounter cost overruns and schedule delays if these geotechnical obstacles are not planned for. We have certainly learned better how to dig tunnels through hard rock since finishing the Red Line, and the existence of the Georgetown Intrusive Suite should not deter us from building this new line today.

A potential solution

WMATA plans to build the new line in stages, with the core segment from Rosslyn to Union Station being one such stage. This section presents the greatest geotechnical risk to the project, but also the greatest demand for additional capacity.

Therefore, I propose that the Rosslyn-Union Station stage should begin construction first, with the expectation that it will take the longest to finish. I also echo calls from other writers that the core segment should be built with long-range planning in mind, including future proofing for full capacity operations.

An article in Adam Bressler’s recent series suggests one possibility: a pocket track between Rosslyn II and Arlington Cemetery to permit turnback operations. Many other possible solutions exist and deserve study.

WMATA could conduct a cost-benefit trade analysis of various depths for the Rosslyn and Georgetown stations, including both bridge and tunnel crossings of the Potomac. No matter how deep, the Georgetown station should get the waterproofing barrier that Van Ness and Cleveland Park lack. At each end of the core segment, diverging stub tunnels with tail tracks could be built to enable future lines in multiple directions, similar to those built at the southwest end of Pentagon for the still-unbuilt Columbia Pike line. At Rosslyn II, track connections could be built to both the Orange and Blue lines south of Rosslyn I, for maximum operational flexibility. At the other end, the new Union Station platforms could be staggered in elevation to accommodate similar diverging tail tracks.

A conceptual sketch of what this Union Station might look like underground is shown below.

Image credit to A. C. Gerhard, on commission. _600_719_90.jpg)

These additional features might marginally increase the cost of planning and building the initial stage, but they allow the most challenging segment to be leveraged for future expansions without costly retrofits.

For example, if WMATA selects the Blue Line Loop alternative now, an Orange Line connection at Rosslyn II and diverging stub tunnels at Union Station would allow the Silver Line to Greenbelt or New Carrollton alternatives to later be built in addition. This would also prevent the alternatives selection process from devolving into a competition between neighborhoods to see who gets a new Metro line. Port Towns and Ivy City needn’t be pitted against Congress Heights and National Harbor, when all four communities stand to benefit tremendously from improved transit.

Decisions about precise location of infrastructure will not occur until the Tier II Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) or NEPA review, which would begin after alternative selection this summer. Nevertheless, BOS planners have indicated at public meetings that elements from multiple alternatives could be mixed and matched, if that is what the WMATA board wants.

The WMATA Board should therefore direct Metro planners to comprehensively study the future proofing options described here, along with any others which would maximize the new line’s capacity, regardless of which alternative they select.

But no matter what, the most important thing is that a build alternative actually gets selected and built. DC needs more Metro: more frequent trains on the current network, and more lines to places the current network misses. Let’s plan for a sustainable future, with a million riders a day on an expansive Metro network, not just one new line.